Eczema is a common medical condition – 1 in 10 adults in the UK currently live with it.

It’s also a very individual condition. There are different types of eczema, different severities, different symptoms, different causes and different treatments. For some people, eczema is just a nuisance. For others, eczema can be all-consuming – debilitating, exhausting and unbearable. For a long time, like many people, I didn’t fully understand this.

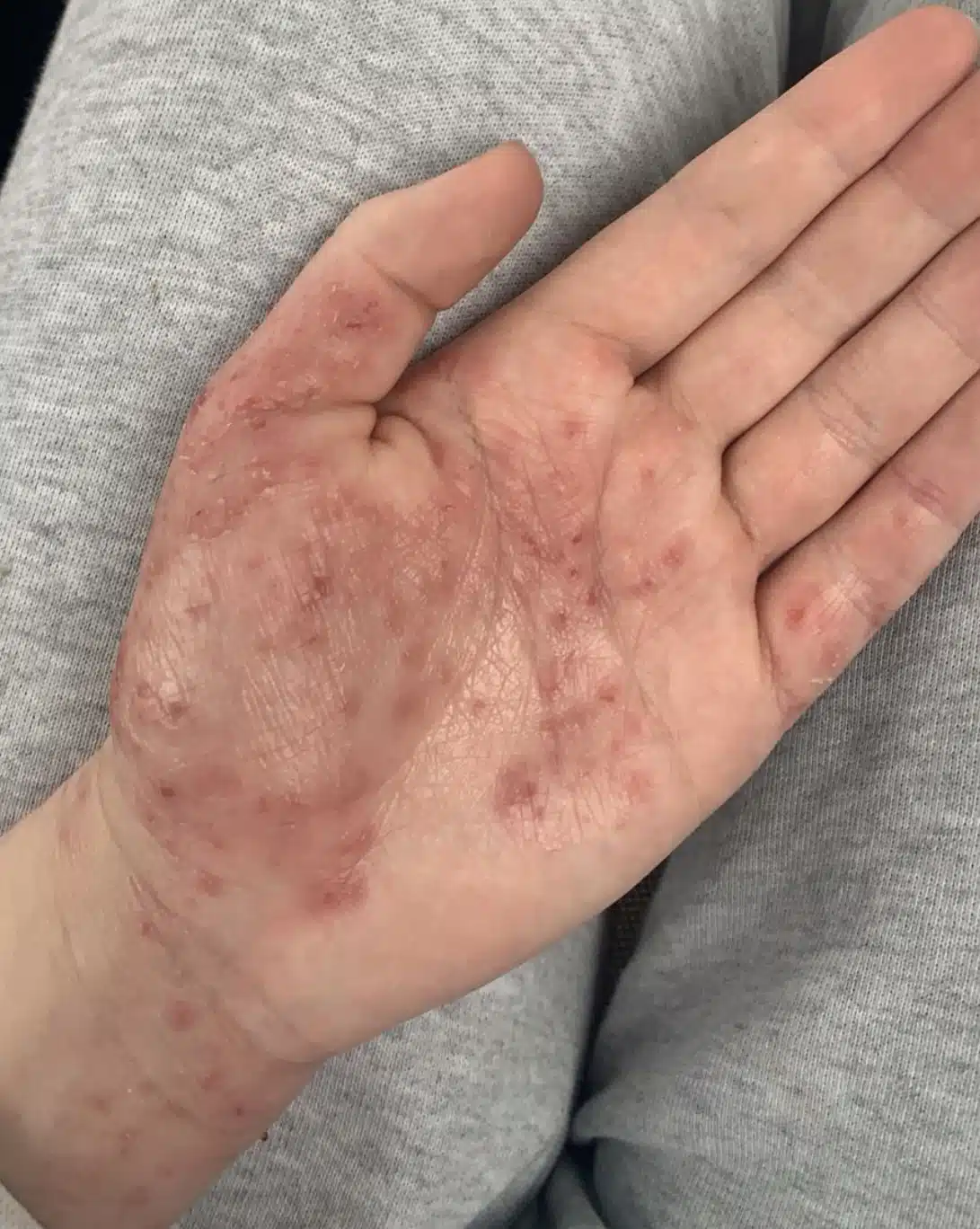

I’ve always had eczema, but it became much worse when I began university. The feelings of stress and excitement every first-year student experiences seemed to map themselves onto my body. I had flaking, dry skin, often weeping and bleeding. If you think this sounds disgusting, believe me, I did too. It was not something I wanted all of my new friends to see.

I became a master at covering my eczema up. Beneath my outfits I was smothered in oily steroid cream and mummified in bandages (to prevent this cream from sticking to my clothes). This allowed me to hide my eczema from my friends, and to an extent, from myself. Of course, this wasn’t always possible. At a university formal, my friend and I both felt quite awkward when he asked, very genuinely, if I had spilt red wine all down my arms – having no idea I was covered in something slightly less tasty.

In addition to bruising my confidence, my eczema stole exciting opportunities from me. I was proud to have been selected to join the university’s rowing team – excited about meeting new friends and the prospect of racing in events like the Henley Regatta. I loved rowing but holding the oars with my hands covered in eczema was really painful. My eczema worsened, and it became increasingly hard to use my hands at all. I couldn’t write and could hardly type. This became unbearable, and after a few months I had to stop. I had never discussed my skin with my rowing coach and thinking that ‘eczema’ was not a valid enough reason, I made up an excuse for why I was stopping.

This inability to accept and communicate to others the severity of my eczema continued throughout most of my university experience. I was reluctant to tell people about my skin largely because of embarrassment, and a concern that people would be ‘grossed out’.

In addition to bruising my confidence, my eczema stole exciting opportunities from me.

My eczema was most severe in my final year at university. The normal stresses of third-year study – harder content and writing a dissertation – were compounded by the fact that my entire body, including my face at times, was now completely covered in eczema. I tried my best to ignore my eczema, focussing instead on securing a graduate job and doing well in my studies, but that, of course, was impossible. The pain of my eczema made it really hard to sleep and I felt constantly tired and unproductive. Moreover, with my skin barrier compromised, I wasn’t retaining heat properly and always felt freezing. Instead of going to the library with my friends, I often had to work in my room, cocooned in blankets – and sometimes, to the amusement of both myself and my housemates, even a woolly hat.

Most challenging was the unpredictability of my skin. Some days my eczema would be manageable, and on others it flared up violently – with no clear reason as to why. The condition of my skin when I woke up dictated how my day would unfold. When I had severe flare-ups, it was difficult to even leave the house. It was painful to get dressed, painful to shower, painful to move.

I remember having an important interview and spending the days before anxiously hoping my skin would behave. Inevitably, it didn’t. I attended the interview on little sleep, concerned the whole day that my interviewers would notice my bright red, eczema-covered skin. During my January exams, I had a particularly bad flare-up. These exams were timed assessments, where I had three days to answer two questions. I couldn’t stop itching and the pain made it impossible to sleep. The timed nature of my exams made this especially challenging. To cope, I spent each day sat at my desk, covered in cream and bandages hardly moving. At night, I had to take strong sleeping tablets to ensure I could be productive the next day. Though I did well in the exams thanks to my perseverance, it came at the expense of my mental and physical health.

Shortly after these exams, I went to visit my dermatologist, who told me my skin was failing. The only reason I wasn’t hospitalised, he explained, was because my skin had been failing for so long that my body had adapted to cope with it. To treat my eczema, I was put on immunosuppressants. This was a wake-up call for me – I don’t just have dry skin that I can try and ignore, I have a chronic illness that will likely never go away and will require ongoing management for the rest of my life.

To cope, I spent each day sat at my desk, covered in cream and bandages hardly moving.

Finally, I reached out to my university and explained my condition. I was struck by how supportive they were, even more struck by their suggestion that I perhaps take a year out to recover. Though I decided against this, I found their support validating. No longer did I feel, as I had in my first year, that I was being overdramatic, and that eczema was not a valid reason for support. The university constantly checked in with me and offered help, including extensions on coursework. With this support, I graduated this summer, and due to the success of my immunosuppressant therapy, I have enjoyed a relatively eczema-free summer spent celebrating.

As a graduate, reflecting on my time spent with eczema at university has been really important. I’ve had to cancel plans to go travelling this year, as missing hospital appointments means I cannot get the treatment I need. The harmful long-term effects of immunosuppressants mean I have to come off them soon, and I don’t know how my body will react to the next round of treatment. With this uncertainty, I worry about my eczema returning and how this could affect me when I start full-time employment.

Amidst these worries, I am immensely proud of myself – not just for my perseverance, but for reaching out and asking for help. I only wish I had done so sooner.